Bicycling Sumatra

The Ultimate Challenge

“Padang, Sumatra was fresh out of the history pages. Horse drawn carriages and rickety bicycles outnumbered cars. Buildings leapt to three stories before culminating in the famous horned roof of the Minangkabau people. Fresh paint had long ago faded under the tropical sun; board siding, eaten by salt breezes, held leaning frames together. Storefronts had no fronts; flies, people, pigs, chickens and dogs entered and exited freely. No one seemed in much of a hurry. It was too hot! For a capital city of 700,000, squeezed between the Indian Ocean and the Bukit Barisan mountains, it emanated an unexpected quiet quaintness.”

“Run down hotels fit right into the general street scene. The lobby’s worn furniture looked like Don Quixote used it for dueling practice. The carpeted floor rotted into the wood boards and reeked a mixture of molded odors. The dingy gray plaster cracked in parallel to the twist in the framing.”

“Our room suffocated in the mid-day heat without the benefit of opening windows or fan. Off-gray sheets disguised rock hard mattresses. The floor toilet blocked the entrance to the bathroom requiring a careful step over if tooth brushing was the goal. All this luxury cost $12.00, about double what we had paid for equal facilities in remote Java. We fled the room’s dinginess to browse the scorching city streets.”

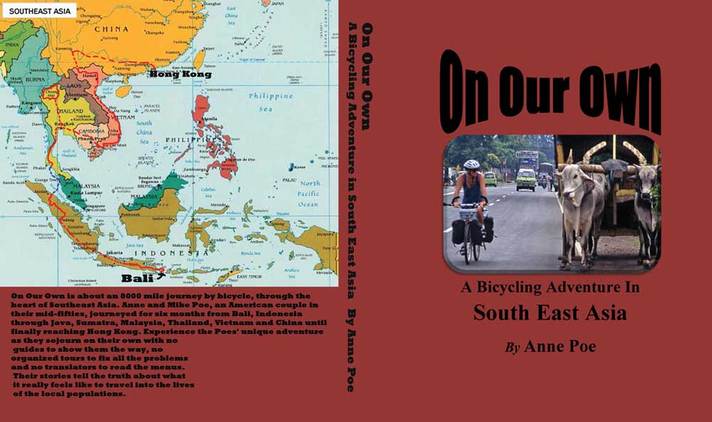

Excerpt from On Our Own A Bicycling Adventure in Southeast Asia

While Java presented a more uniform cultural experience, Bicycling Sumatra was like moving through a mosaic of hundreds of little principalities dominated by different historical tribes. Every day we might cross an unseen boundary. We found ourselves in a culture where women ran the show and husbands were banished from business. Inheritance passed down through the female line and men moved into their wives houses.

Another day brought us into warrior country where men took to the streets, yanked us off our bicycles or blocked our way with a human barricade, not to confront us, but to shout “Horas!”, or hello much in the way of the Maori of New Zealand.

Bicycling Sumatra meant getting sick everyday on the food which became a serious challenge.

Markets sold meats, and fish without any refrigeration. Quick trips into the jungle followed every meal until we literally stopped eating everything except plain rice.

Which brings up another important topic when bicycling Asia…

the floor toilet.

“In Asian home and shop life, furniture may not be considered a necessity. Much activity takes place at ground level, which for centuries has honed the art of squatting. To squat properly, the feet are hip width apart, flat on the floor and pointed straight ahead. The buttocks are lowered to within four inches of the floor, the knees somewhere around the shoulder area. As one is well balanced and comfortable, the hands are free to do tasks like cooking or shoe making or chatting. Having acquired the balance, suppleness and endurance to squat from early childhood, it seemed natural that the toilet system makes use of such a common ability.

“This awareness invented the floor toilet. Most of the toilet facilities we knew personally in Asia were pre-formed ceramic oblong bowls sunk level in a rough concrete slab. The toilets never flushed. Water came from a nearby bucket; debris was encouraged to exit by sloshing. Sometimes the final resting place was just on the other side of the wall.

Incorporated in the toilet rim were two widened areas with raised ridges. The outlines suggested in any language where and in which direction to place your feet, which was critical to a proper aim. Sometimes the prints were too small for our bigger feet. Always the prints were dead arrow straight ahead, which stymied my duck-toed inclination. This problem worsened when the toilet rim was set six inches above the concrete. The cliff-like drop left no room for accidental slippage.

Now came the tricky part. Unyielding thighs, dead tired and stiff as boards from riding, a steel rod lower back and Achilles tendons shortened by hours locked in pedals suddenly needed to flex and balance in a manner far beyond historically programmed activity.

Since the hands were occupied pushing the walls apart, wiping became more of a challenge.

Excerpt from On Our Own A Bicycling Adventure in South East Asia

“Bukittinggi’s charm held us captive for three days. For beyond the comforts of the travelers’ enclave, the town exemplified a more traditional character. Horse drawn buggies offered public transportation, though most the streets filled with pedestrians. Ladies framed in head shawls clung together like jam and peanut butter as they flitted through the crowded market place.

A demure Muslim girl approached with uncommon certainty. She reached into the deep folds of her full-length skirt and pulled out a small object.

“Excuse me,” she said in a soft friendly tone. She raised the object to my view. “I would like to take your picture.”

I was certain my bicycle shorts and T-shirt, my blond uncovered head and white skin would generate stories for years to come, just as a photograph of them would occupy a place of honor on my coffee table.

In the midst of fulfilling my photographic desires, I frequently fretted about the unevenness of the situation. I asked myself how I would feel if people came to my hometown and pointed their cameras at me. I knew my response would fall in the category of “hey, who gave you permission?”

I could however balance the seesaw through a different rational. My presence in the Third World always promoted legions of staring eyes, more penetrating than any camera. The local people constantly invaded the personal space that was so sacred to my lifestyle. I did not relegate these offences against me to retaliatory thinking. Rather, the experience of them created a greater sensitivity in me towards intruding with my camera. I struggled constantly to bring courtesy to the process.

The seesaw dropped me with a thud as I realized the impact of being on the other side of the camera. I felt honored to be the subject of the ladies coup, and bewildered that it could even happen. It opened my mind to the generic curiosity of all human beings and our need to fashion understanding out of difference. Staring and picture taking were partners in the same process.”

Excerpts from On Our Own A Bicycling Adventure in South East Asia

“Can I help you?”

The accent was decidedly San Francisco. We raised our squinted gaze from the tiny print in the pages and focused on what could only be described as a hippie. His disheveled hair found order through the benefit of a beaded necklace serving as a ponytail wrap. A frenetic beard equalized the weight fore and aft, while the single loop lead earring tended to list his head to the right. A billowing natural cotton sack flowed graciously over his bony shoulders before falling captive to a brilliantly woven woolen sash.

“We are looking for a cheap hotel.”

Samuel was from San Francisco, on his way to Lake Toba after wandering Malaysia for six weeks.

“I have a spot just a couple blocks from here. Fifteen dollars is steep, but it was all I could find. It’s a bit like lookin for a roost in Frisco without a friend.”

“Thanks, we’ll check it out.”

“Come out of Sumatra have you? I heard it doesn’t really fit in the tourist scene. I plan to hitch hike my way to Bukkittingii. Sounds like an out-of-the-way place.”

“Three weeks bicycling Sumatra flashed before my eyes on an IMAX screen.

No Samuel, it doesn’t fit the tourist scene. Living room parlors, kitchens and bathrooms spill into the streets; frantic, undisciplined children and adults charge and grab at you as if you are the circus that came to town. Muslim Mosques deafen you into prostration; unsanitary food preparation poisons you into weakness. Noisy uncomfortable hotels and filthy bathrooms breed mosquitoes and sleepless nights.”

“Mile after mile of sweet smelling, rain soaked primordial jungle, cascading, tumbling, rumbling free running rivers, wild parrots, monkeys, tigers roaming as intended … one of the few balanced places left on earth … nourish your soul. Volcanic craters: the biggest blast, the deepest hole, the most devastation … the Guinness Book of Records could highlight Sumatra … still wild, still natural.”

“We ran to it; we ran from it. Sumatra uncovered intense frustration and quickened us to unfamiliar depths of anger. It lifted us to immeasurable joy; it gifted us greater patience and understanding. It pummeled us into physical exhaustion with its plunging gorges and steep twisting mountains and raised us above our self-imposed limits.”

Excerpts from On Our Own A Bicycling Adventure in South East Asia

By Anne & Mike Poe

Copyright Material

All rights reserved. No part of this page may be reproduced or utilized in any form by any means, electronic or mechanical, including downloading, print screen, photocopying, recording, or by any information storage or retrieval system, without the prior written permission by the copyright owner.