On Maya Time

Bicycling Belize from Village to Village

Belize is not a typical Third World country. Instead of exploiting its people and resources, it is working to find ways to profit by preserving them. With 60% of its ancient rain forest still intact, and most of its indigenous Maya groups living autonomously, the effort is showing promise.

Today’s Maya live traditionally, in scattered villages, gathering their needs from the rain forest. They grow and make practically all they need to live. But their way of life is threatened by their own practices., as soils degrade from slash-and-burn farming. They need another source of income.

The Belize government has come to realize that preserving the natural habitat of its country can bring needed dollars into the economy through small-scale tourism. Together with the Maya, they created the Maya Village Homestay Network, a system for preservation and income.

We could hear the women laughing, and smell the freshness of the cool river water through the dense heat and greenery of the rain forest. Our bikes bounced around on the rough road as we rounded a corner and braked to a stop on the bridge. The women looked up from their laundry and bathing and demurely greeted us in perfect English.

“Hello. Are you going to stay in our village?”

My husband Mike, and I had driven from Idaho to Belize with our mountain bikes in tow. Now we were looking for a special place to unload the bikes, and found it in the thick forest of the Maya mountains of southern Belize, where 30 traditional Maya villages nestled in obscurity. Ancient ruins barely reclaimed from the jungle, unpaved roads with minimal traffic, these were the catalysts for our ten day adventure.

An unexpected bonus came in the form of a fledgling home stay and guest house program; while we cycled from village to village, we would stay with the Maya in their homes, and learn about their culture.

On the bridge, it was 85 degrees; moisture hung in the air like gauze, and road dust clung to our sweaty bodies. The women’s friendly welcome was too tempting for me to pass up. Dropping my bike on the roadside, I jumped into the river—, clothes, sandals, visor, grime and all.

The ladies, naked from the waist up, offered me their bathing soap, along with giggles and stares. It was an event that would repeat itself several times a day, as we cycled through Maya land. The cool refreshing streams meandered throughout the area, offering respite from the heat and a chance to meet the locals.

We had arrived at the outskirts of Laguna. It is the pilot village for the guest house program. Each village has voted whether or not to build a guest house for visitors.

To create a guest house, a traditional thatched-roofed dwelling is split in half, one side for male visitors, one side for female.

Vincente Sacul greeted us as we rode down the grassy lane to the village. We were the only foreigners to come to the village in several weeks. Though the program is several years old, it is still in the trial-and-error stage.

The goal is to protect the village from too much tourist intrusion, yet provide them with income from tourist dollars.

Two young ladies, grimacing under the weight of five gallon buckets filled with fresh cold spring water, but smiling ear to ear, carried the water into the bath house.

“You must be tired and dusty from your long ride,” one of them said. “Come and refresh yourselves.”

The next morning, Vincente and his son met us to take us on a tour of his farm. We cycled up the grassy road a few miles, Vincente and son on their one-speed, we with our 15 gears. We dropped our bikes on the roadside, and they led us into the jungle. A tiny path had recently been cleared with machetes. We entered a botanical garden of unfamiliar shapes, colors, and odors. To Vincente, it was his storehouse.

“The women take this leaf and strip it into narrow pieces to make their baskets,” he said, using his fingernail to cut the long leaf into quarter-inch wide strips.

Vincente moved a few feet farther down the path, singling out two more plants.

“We take the roots of this plant to make the rope that ties the palm leaves to the roof rafters,” he said. “And over here, this is the tea you had for breakfast.”

For Vincente, it was like walking down the aisles of Wal-Mart.

“We use this plant to make the wicks for our kerosene lamps,” he said.

Finally, after more than 30 minutes, we came to something I recognized— corn. Vincente had cleared the tall trees and planted a grocery store in the midst of the debris: papaya, mango, plantain, rice, yams, and lots of corn. Jungle vines and plants swarmed around his stalwart crops.

There are Roman roads, and there are Mayan roads. Romans built their roads out of flat rocks, pieced together like a mosaic.

Modern-day Mayans built their roads out of big, angular rocks, dumped out of the truck and left to settle on their own.

There were lots of sections of packed dirt roads as well. These were perfect for mountain bikes with knobby tires.

Bicycling Belize

Another cool bathing river, filled with laughing children, announced our arrival at Silver Creek village. Silver Creek had not yet decided on a guesthouse or home stay program, so our arrival caused more of a stir than we experienced in Laguna.

We asked permission of the village leader to camp. He offered us the school playground.

Silver Creek Village

I opened the tent door and invited them to look in. Like the telephone booth contests of yore, the kids scrambled to see how many of them could fit in our tent. The Thermarest mattresses became instant trampolines, as our bicycle helmets made their way from one little head to the next. Soon, more kids came running, squealing in delight. Now there were 30. When the adults came, we thought we might get a reprieve—but they crawled into the tent too! But when Mike took his bath out of a bucket of water, the children were reduced to quiet wonder.

San Miguel

The Mayan villages were not very far apart, but the riding was tough nonetheless. We thought we were in for an easy day, as the route from Silver Creek to San Pedro Columbia was on a dirt road through rolling hills rather than the rugged rock surfaces we had been riding, but it rained in the early morning hours, turning the road surface into a sea of goo. We could not even coast downhill as the mud clung to our tires like Velcro.

Many Maya use bicycles for transportation, and we were encouraged to see these toughened riders cleaning the goo off their tires along with us. Misery does love company.

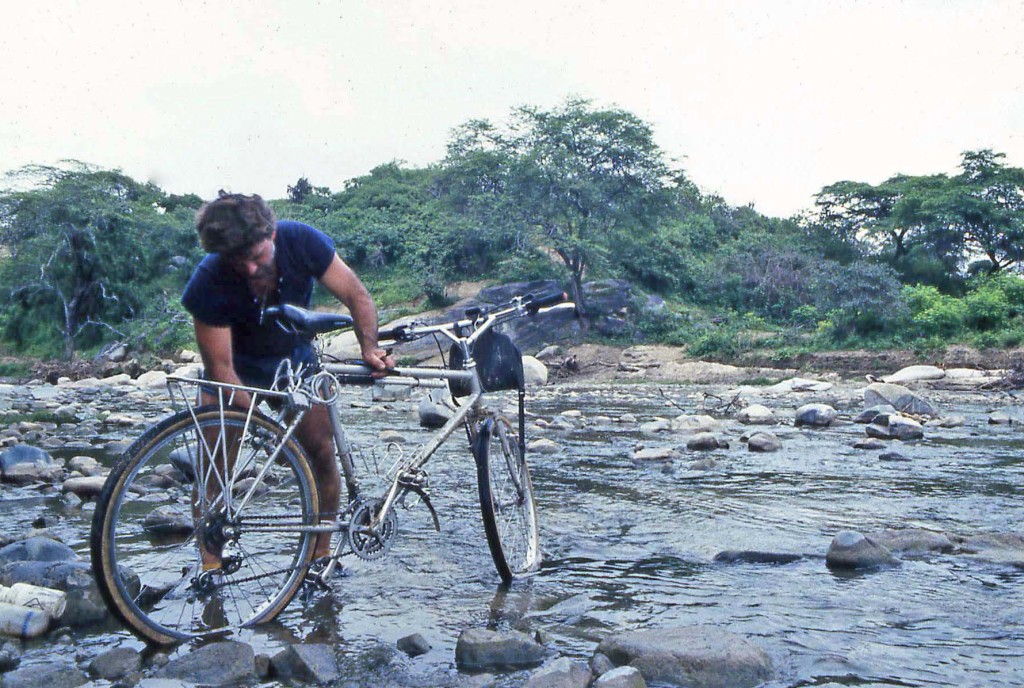

We pushed our bikes six miles to San Miguel, were we jumped into the river for a refreshing bath. The questions from the villagers started coming fast and heavy.

“Where are you going?”

“Where did you come from?”

“Would you like to stay in our guest house?”

The charming town of thatch houses, friendly people and beautiful scenery were reasons enough to stay in San Miguel, but it was only 9 a.m.! We declined the gracious invitation we had received, explaining that we were going on to San Pedro Columbia.

The road dried out under the rising heat. We were riding again. We came to the Lubaantun ruins three miles beyond San Miguel. The ruins have barely been reclaimed from the jungle; the remaining walls have been untouched for centuries.

Perfectly cut stones are stacked like hay bales; the Maya use no mortar.

We reached San Pedro Columbia in the early afternoon, where the heat made a swim mandatory. Many villagers were washing laundry, bathing and frolicking in the river. We joined them for the remainder of the day, and stayed at their guest house that evening.

As we rode deeper into the mountains, we could feel the remoteness surround us. The jungle closed in, as each hill became an individual “Everest to climb. It was hard to keep the front wheel pointed ahead at such slow speeds.

Much to our surprise, we noticed on one of the climbs, that two young Maya ladies were running up the steep road behind us. We had passed no houses; we were near no villages. They called and waved at us as they ran barefoot on the rough rocks.

“Would you like to buy our blouses?” they said simultaneously.

How far could they have been chasing us? And how could we resist buying their beautiful, handmade blouses?

Bicycling Belize

The guest house in Santa Cruz was just a few miles from the Guatemalan border. Marcos, our host, extended a warm welcome, and a cup of tea. The people in his village were descendants of refugees who fled from the overwhelming brutality directed at Mayas in Guatemala.

The women were up at 4 a.m. They needed to grind the corn and cook the tortillas for the men to eat in the field. Maria taught me how to grind the corn.

It takes two hands, and a foot brace to push against, to gain the advantage over the toughened kernel.

Mine are too thick. It’s hard to get them right, but Maria continued to encourage me.

Santa Cruz Village

It was rice planting season, and the men left their homes early to cut down the rampant jungle growth overtaking their milpas. They would cut and clear with machetes for a month, then plant their precious crop. Families joined together to ease the burden of each man’s work. Marcos invited Mike to help.

Deep in the mountains, you can lose your tourist status, and participate in the realities of Mayan life!

We left our panniers with Maria and Marcos, and set off the next morning for Santa Elena and Pueblo Viejo on a day excursion. The road deteriorated into a jumble of jagged, unstable rocks. It was as difficult to work our way down the steep hills as it was to struggle up them. We were winding our way deeper into remote Maya land.

Dionisio and his family welcomed us to Santa Elena. They offer tourists the opportunity to sleep in a hammock in their home. We had to decline, but spent an hour cutting and clearing a corn patch from the jungle with them.

The roughest road of all extended from Santa Elena to Pueblo Viejo at the Guatemalan border.

While Europe was muddling through the Dark Ages, Mayan civilization was creating astronomical charts, calendars correct to the second, trade routes across the continent, timeless sculpture and music, and religious rites and ceremonies still adhered to by today’s Maya.

The Maya’s tenacity to survive is a historic fact. They have fought efforts to change them since the European invasion.

After visiting among them, I can only confirm what Marcos had said to me when we were leaving Santa Cruz, “Time is our ally. We are Maya.”

Bicycling Belize

Guesthouse and Homestay Programs

At the time of this writing in 2000, there were two visitor programs to choose from when visiting Maya villages: guest house and home stay. The guest house program allows visitors to stay in a separate building built by the community. Both visitors and visited have more privacy. A rotation system for providing meals guarantees the villagers an opportunity to share in the profit.

The home stay program allows visitors to sleep and eat in a Mayan house. There is less privacy for both parties, of course, but you really are in the thick of things.

For more information contact: Toledo Ecotourism Association, 65 Front Street, Punta Gorda, Belize, CA. In Belize call 0-722-096. From the US call 011- 501-722-096.

BY THE NUMBERS: Belize is about the size of New Hampshire, and has a population around 200,000; the Maya comprise about 6% of this population. The country has a parliamentary system of government, and the official language is English. The currency is the Belize dollar.

AIRLINES: Continental (1-800-231-0856), Taca (1-800-535-8780, and American (1-800-433-7300) fly to Belize City. Check individual airline rules for bikes as baggage. There are six flights and one bus daily from Belize City to Punta Gorda. And remember, you need a passport to visit Belize.

CLIMATE

The climate is subtropical, with a dry season between late January and May. Average daytime temperature is 80 degrees F.