Bicycling Panama

Crossing the Border with Bicycles

A first border crossing is always an unknown. When traveling without a guide and speaking a new language, it can be downright frustrating. Patience is the key. A lot of patience!

We got in line at 8 am, along with a busload of tourists. Instead of standing in the long line, I went around to the back door, stuck my head in and asked for the inspector.

“Atras” the man motioned. Since there was no “atras” (behind), I was a bit puzzled and asked again. There was no office, just a couple of bathroom doors, a cafe, and a closet door. The helpful man waved me “atras” again.

On the third try, he got up and opened the closet door. There was the inspector!

“Please forgive my poor Spanish”, I began. “Yesterday we came to the border on our bicycles. The officials told us we needed a tourist card to pass into Panama. They told us that you would be in the office today and could process the tourist cards. It would be a very long bicycle ride to Neilly to get the card there.”

“No problem”, he said. “Give me your passports.” I smiled a sweet, patient smile all the while.

“I have a problem,” he said rummaging through his desk. “I have no tourist cards.”

I remained calm. He rummaged some more…maybe fifteen minutes…looking for a bribe I figured.

Finally, he came up with two used tourist cards. I smiled in appreciation.

He erased the information on the cards and replaced it with ours. The he stamped his rubber stamps all around to cover up any missed steps.

“They have bicycles,” he informed the official. My new helper filled out the bicycle forms in quadruple. Name of bike, serial number, color, make, model, year, axel size.!!!

“Three dollars each please.”

I explained I had no Panama money and needed my passport to go to the bank. We had travelers’ checks. One hour later, I succeeded in getting money and scurried back to my man.

“Good. Now go to Policia with these papers.”

Policia copied by hand the exact same information that was on the quadruple forms.

“Now go to this office over here to register the bikes.”

This man copied everything again into his notebook.

“Have a good trip,” he said.

“We can cross? Nothing else to do?”

“Yes, of course,” he replied.

Two and a half hours turned out to be a fast processing time. We went to the duty free store across the street and had breakfast at the cafe. Upon returning with our stamped paperwork, another official stopped us.

“Passports please.” He waved us inside. He wanted the same damn information all over again. He copied it laboriously into his logbook.

“Two dollars please.”

He picked up the business end of a disinfecting machine and smothered the bikes in goo before we could object.

Disaster Strikes

We rode all afternoon to the city of David. We checked out a few motels and decided the $12 price for the same $3 room we got in Costa Rica was too high. So we rode out of town to look for a place to camp. A tavern advertising tourist amenities drew us in. We talked to a gentleman.

He owned all the land behind the tourist facility and said we could camp there.

Shortly after, a young lady, the man’s daughter came by to welcome us.

“We live on the other side of the field,” she said. If you need anything, just stop by.

We fixed supper and wrote in our journal. After dark, she came back on her bicycle, with her two daughters.

They invited us to come to their house for a spell.

The two older brothers offered us drugs, which we readily declined.

When we got back to camp, we locked the bikes to the steel post beside the shed.

Loud music from the disco played all night.

Our packs were quickly ready to load onto the bikes. Mike turned toward the shed to unlock them.

He stood in silence, not moving.

Our Bikes Were Gone!

With the loud music all night, we could not have heard the thieves cut the chain or break the lock. We confronted our hosts, certain the boys had stolen the bikes. They had examined them closely the night before and even asked if we would sell them. They tried to encourage us to smoke Mary Jane which would have aided our deep sleep. A blanket from Jaime’s truck lay on the ground near the theft. It was not there when we went to bed. The boys had disappeared.

The sister offered no assistance of any kind, rather wanted us to go away; we felt indeed they did it.

The hurt was deep…our first experience with deception. It would not be our last. Many more people on our journey would try to steal from us.

Panama City

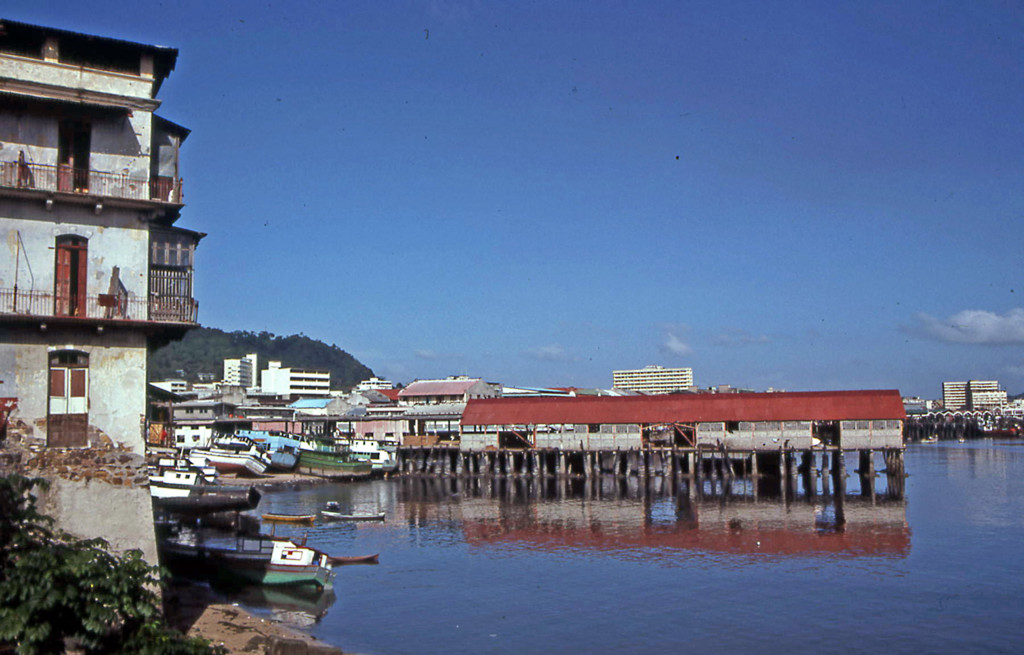

We caught the bus that day to Panama City. De-boarding in the heart of the city, we felt very vulnerable being so heavily laden with panniers. This certainly marked the beginning of our newly discovered paranoia. We suspected everyone of wanting to grab our gear from our arms. We took a crummy hotel in the old part of the city and went out for a good dinner. Somehow, a good dinner out always helped when things went bad.

We called Pack & Paddle. They could get bikes for us… and were happy to give us 20% off… but at least they could order them. It would be a week.

We moved to a cleaner hotel in a safer part of the city. Mugging was reported as a favorite pastime as the first hotel manager had warned us not to go out after dark. It was the old, historic center of Panama City; the Presidential Palace and many more national monuments were in this crime ridden area.

We had a week to explore Panama City. The new city was built with American money. Large high rise buildings, apartments, and fancy hotels were owned by Americans. It was very expensive. Restaurant prices were high for poor quality meals. The best buy was McDonalds: $4 for two hamburgers. Clothing, furniture, electronic goods were all imported from the US.

The local population lived in great poverty and filthy living conditions. The gap between rich and poor festered the high crime.

We never did find a tourist office or maps of any consequence. We had our Lonely Planet guidebook for Central and South America. It was the bible of that day. It gave us a few clues where to go.

Sunday morning everyone went out for a stroll. We decided to get what photos we could of the city just one day as we did not want to be spotted with an expensive camera. We walked down a wide, open street in mid-day, heading for the main market area. I held the camera close to my side, tucked securely in my arm and holding the lens tight in my hand. The strap was around my neck and under my shoulder. We knew thieves used razor blades to cut straps from around tourists’ necks.

When we wanted to take a picture, Mike glanced around before leaving my side.

Walking together again, I thought Mike tugged on the camera because he wanted to take a picture. In quick succession, the tugging persisted, strong and fast.

I realized someone had snuck up behind us and was trying to pull the camera from my hands.

Mike was hot on his tail, but backed away when the kid ducked into the dark alleyways.

Bicycling Panama

Panama City into the Darien Gap

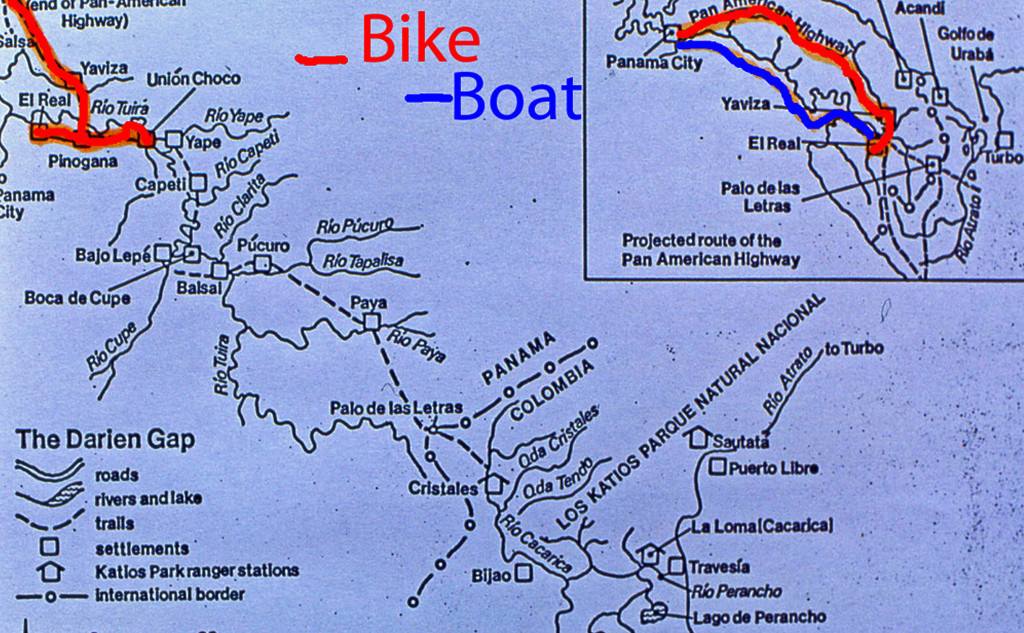

We planned our entire bike journey from Central to South America to cycle through the Darien Gap from Panama to Columbia.

This infamous 180 mile stretch of wild jungle had yet to be pierced by a real road.

Many adventurers had put together expeditions to conquer the Darien…all had failed. Travel was by rivers. Roads that did exist were really swamps and mud holes.

We thought bicycles had a better chance to make it through than jeeps or big vehicles.

Trial

by Jungle

An Attempt To Cycle

The Darien Gap

BY ANNE POE

We pedaled 400 yards.

“Which way?”

“Let’s try left. It should follow the river.”

Down a muddy, root-bound trail we bounced and slid for a mile. The trail ended. It took an hour to push back up to the fork. We took the right. The trail deteriorated. Another fork. The map showed no forks. Compass in hand we headed east, to Union Choco, we hoped.

The light faded as we moved deeper into the jungle. The rain was deafening. The trail snaked like a roller coaster. Mike had to help drag my bike through the unyielding mud, It was like pulling on a defiant mule, its knees locked against progress. Left, right, turn, twist- the trail had no sense of direction. Creeping vines snagged the pedals; mud clutched the wheels. We pushed to the top of a hillock where a break in the canopy allowed us a look outside our confinement.

No river, no sign of the trail, just rain, trees, rain, trees – forever.

Trying to ride mountain bikes through a 180-mile road less jungle between Panama and Colombia was something like the Donner party trying to cross the Sierra snow in wagons. Panama has historically declined Colombia’s pressure to build a road, citing the jungle as a buffer zone against the spread of foot-and mouth disease. So access to native villages has been by dugout canoe and trails wrest from the jungle by machetes.

We were not members of that macho masochistic set, the “no pain, no gain” bikers. We were just an ordinary couple, the two week-tour-a-summer sort, looking for a little change of pace. Something with a dash of foreign, a sprinkle of adventure, and an overall dose of wilderness.

There was even a measure of planning to all this- some Spanish lessons, trips to the library for The Jungles of Panama, Chiggers, Ticks And Vampire Bats and Primitive Tribes Of The Darien.

It was getting dark; we needed to camp, but where? We plodded on in hopes of finding higher ground. Instead, our trail disappeared, banked two feet high with mud. The center was under water. Trees crowded in. There was no going around.

I leaned against my bike…defeated.

Tiptoeing across a three-inch-wide steel rail bridge was like balancing on a greased tightrope.

Forty pounds of panniers didn’t make maneuvering any more pleasant.

It had taken four grueling days to drag our bikes 21 miles. When the highway ended 220 miles South of Panama City, so did our optimism.

Clouds thickened and it began to pour, jungle style.

Yavisa was catapulting itself toward the 20th century. Power lines, T.V. antennas and a bright yellow Chromos film developing booth testified in favor of progress. Gold, green and pastel blue paint splashed the fronts of wood framed houses thoughtfully constructed three feet above the forest floor. Behind were carefully tended fields of platano (large bananas that must be cooked before eating), rice, corn and yucca.

The planters, descendants of escaped slaves over 200 years ago, had carved their new life from this watery land.

Maria spilled out the doorway of her cook house, the best and only place to eat in the village. She engulfed my reedy frame in the motherly warmth of her enormous embrace.

Her laughter shook like a bowl of Jello. “Child, you need feedin,” she said with a disapproving look.

Indians of South America say “You have to go to get there.” Though the going was like beating yourself on the head with a hammer, the relief of getting there was like jumping in a hot tub (oh, how we wished). The people of the Darien were as welcoming (each in his own way) as the jungle was hostile.

The village of Pinogana had received us more emphatically.

“I am the mayor. Come to my house and eat,” a Panamanian of obvious authority ordered.

It seemed prudent to go, though we had an uncomfortable feeling we couldn’t identify.

Up a flight of stairs, we entered a dark, musty room. The tiny space was overwhelmed by a nine-foot couch with red velvet cushions, a teakwood dining table and a stereo with speakers. He led us into the kitchen, sat us on wood benches at a miniature slab table. A small piece of rice and fish was already served.

It seemed the fabled jungle drums had announced our coming. It was all too pat.

”Three dollars please,” the mayor smiled as he held out his hand. I hadn’t yet swallowed my first bite.

It was obvious we had become an important source of income for the local hierarchy.

“You are going to Union Choco?” he inquired.

“Yea.”

“I will arrange a boat for you. You pay me $90.”

We were exploitable symbols of wealth caught in a world fast becoming aware of conveniences.

“We’ll bicycle.”

”’There is no trail. You must go by river.”

All that evening we inquired about the village; not a single person was willing to indicate that any trails existed. Now and then, reason becomes a sacrificial victim of bullheadedness and stupidity. Our money-hungry mayor was not going to finance a VCR from our pockets; we would sooner bushwhack.

When we crawled into the confines of our tiny tent, I was certain a dead animal had followed us. But even the fungus growing in the damp bags seemed normal now. The rain pounding on the roof lulled us to sleep.

Our trek to Union Choco was everything the mayor promised it would be. But when we came to the clearing and entered the village, our efforts were redeemed.

Spacious pole houses open on three sides protected from the rain by thatched roofs, perched high above the forest wetlands.

The village chief approached; his dark searching eyes went from Mike’s rough beard to my make shift shoe (the sole of which was inadvertently laid to rest in some mud hole), then locked on the mud caked bikes.

A long, deep, awkward silence followed.

“Where did you come from?” he finally questioned, easing my discomfort at being looked at so thoroughly.

“Panama City.”

Another tedious silence followed as he digested this momentous piece of information.

He couldn’t understand how rich people (and we were rich in his eyes) would want to give up all our comforts and conveniences to seek hardships.

He cracked a smile, the kind that wondered why in any language. But without another word, he motioned us to follow. The concrete slab, waist-high walls, thatched-roof building was their schoolhouse.

We could camp here.

The far-reaching arm of civilization had already found these gentle people. The men were gathered around a large cardboard box.

Inside was a Sony TV for which they could not read the English-Japanese directions.

The next day would be an easy ride; only four miles to the Indian village of Yape. But Daniel Boone couldn’t have littered a trail with better traps. Thorn trees buried in the mud sliced at the tires with their two-inch-long razor-like leaves. My mind conjured up images of quicksand as I struggled against the goo. The straw that finally broke the camel’s back was the 70-pound load of angular metal and bulky packs freeloading on my shoulders. I didn’t fancy exchanging roles with my bike for the next 160 miles. I thought about the Jaibana searching for an easier way.

We accepted our defeat and turned back.

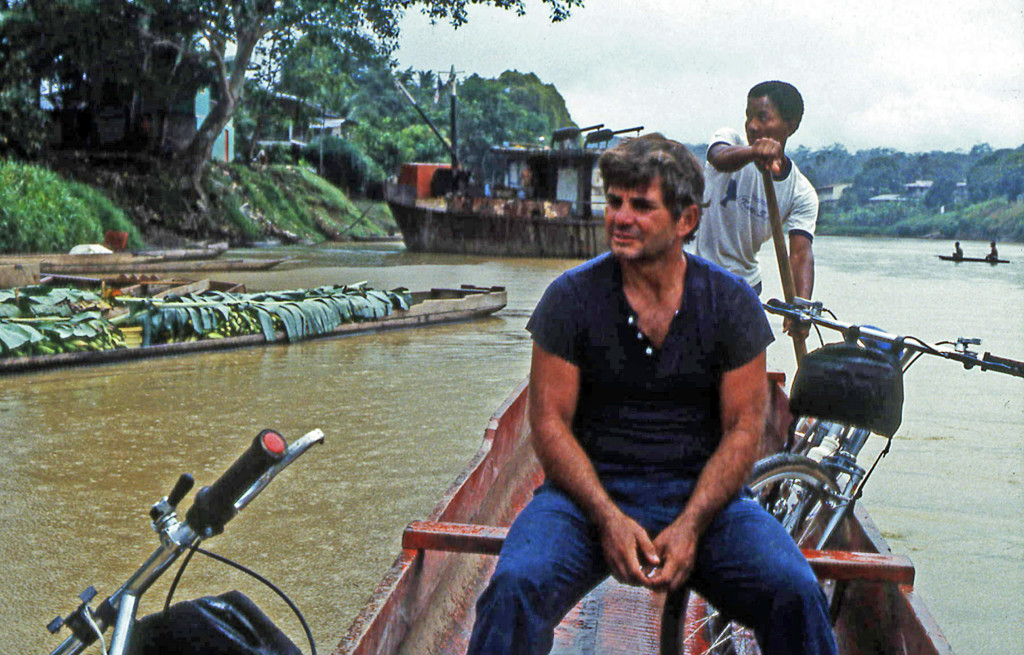

Four days on a 50-foot Panama City-bound floating banana pile accompanied by 6 crew, 14 Indians, countless horny roosters, and a puppy with an active bladder eased our disappointment at not completing our planned adventure.

After all, you are where you are, and an adventure is always what you make of it.

Copyright Material

All rights reserved. No part of this page may be reproduced or utilized in any form by any means, electronic or mechanical, including downloading, print screen, photocopying, recording, or by any information storage or retrieval system, without the prior written permission by the copyright owner.